Having had a thoroughly enjoyable weekend at the Dark Mountain Festival 2011 in Hampshire, I started thinking seriously about researching the Dark Mountain Project as part of my PhD. I spent much of the festival chatting to people about the transformative power of stories and hearing how people are changing their lives based on an understanding of our times as one of unprecedented change (at least as far as anyone remembers). The story of change came in many different shades, and everyone had their own understanding of what is happening, but the background narrative that the socio-economic structures and thinking that underpin our lives in modern society is taking us down a route of social upheaval and environmental destruction was the same.

A couple of years ago, during my master’s degree in climate change, I’d run up against a wall trying to see how we could possibly avoid the disastrous impacts of climate change on our planet (not to mention pollution, peak oil, population growth and over-consumption). As anyone who has really looked into this will tell you, we can’t avoid it. Politicians are scared out of their minds about the change that is coming but they are even more scared about what would happen if the general public get scared too because, well, you know what governments think about anarchy. So, we keep hearing how technological innovation will save the day while emissions keep rising in the never-ending chase for economic growth. The problem is that there is no techno-fix for the mess we’re in and it doesn’t look like such a good idea to keep extending our control of the biosphere. We’ve just got to hang on tight.

That’s not really a cheerful message. And I wasn’t really very cheerful then. The worst thing was that I didn’t feel I could relate to many of my closest friends and family about this. It took a while to come to terms with. When I then encountered a whole bunch of people with whom I could skip the ‘is climate change really happening?’ debate, and jump straight into ‘how are we going to deal with the unthinkable?’ I was, needless to say, both glad and relieved. And, despite the gloomy background story, there was nothing doom and gloom about it. As I wrote in a previous post, I think the Dark Mountain Festival nurtured our collective spirit and brought life to different visions of the future.

Interested in how our exchange of stories that weekend encouraged and strengthened the work we do individually in our different lives, I decided to look deeper into the role of narratives in socio-technical transitions. And what better place to start than Dark Mountain? I wrote to Dougald Hine, co-founder with Paul Kingsnorth, and asked if he wanted to meet for a chat about the possibility of researching the Dark Mountain Project for my PhD. He agreed, and spent an afternoon answering my questions about Dark Mountain and stories of change. What follows is a transcript of our encounter, which Dougald has kindly agreed to being published here. It serves as the basis for a shorter piece about Dark Mountain which will be published on the soon-to-be launched Science, Society and Sustainability (3S) website next month. With more space here to go into detail, I thought it worth putting up a longer version.

JDG: What is Dark Mountain to you as a founder?

DH: A term which I use a lot is conversation. That for me is a way of framing things, because it started as a conversation between Paul and me. We were reading each other’s blogs, commenting on them, getting in touch by email, meeting up in the pub, having conversations. And out of that conversation grew the text which is the manifesto. Now, at the point where the conversation is passing through the bottleneck of a manifesto, it is rather like something going through a megaphone, which is not a very conversational mode. But the purpose of putting it through that megaphone was to broadcast an invitation that would allow a lot more people to join the conversation. I think a lot of people expect a manifesto to be a fixed position which you’re going to defend, but to me it’s more like raising a flag: signalling a place where people can converge, to see where it goes next.

It was important to me that where it went was to return to that conversational quality, rather than a programme to be defended, which is the other direction that something can go from having been framed as a manifesto. And part of that is an openness to the unexpected. A conversation is always improvised, by its nature. And improvisation as a mode of social organisation is one of the things I have been thinking about and reflecting on, in the context of Dark Mountain.

We thought that what we were doing was starting a literary journal, and actually that turned out to be just one of the manifestations of this unfolding, improvised conversation. Because we didn’t expect bands to start releasing music that had been inspired by the manifesto. We didn’t expect to get invited to use the space in Llangollen last year, which is why we did the first festival – we got an invitation from a guy connected to the venue. And so that’s another sense of the spirit of improvisation… a kind of openness to unexpected opportunities, to the thing that matters. Allowing the thing that’s at the heart of it to take forms you’d never thought of, rather than being too attached to the form that you happened to start out having in mind.

Perhaps I could say that the thing at the heart of Dark Mountain is an attitude… a way of being in the world, a way of being together. Each of these manifestations feels right, to the extent that it is a manifestation of that attitude. The manifestation that it was natural for us to expect as a pair of writers was writing. And in the event, that’s turned out to be only one of the manifestations – and to some people that will be the most important part of it, while to some people the community, the events, or the stuff which it inspires that people bring down to a practical, active level of reality, or the transformational experiences that lots of people are having in relation to it, are the most important thing. But all of those are manifestations of this thing that’s sort of… at a higher level, has a certain coherence as a philosophy. Not a philosophy in the sense of a complete set of rational propositions, but a philosophy in the sense of an attitude to life and an attitude to reality and to one’s situation.

JDG: Yes, in your conversation with David Abram [which is described in the article ‘Coming to our (animal) senses‘] you build on the statement in the manifesto that “the end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world full stop” to say that the end of the world as we know it is also the “end of a way of knowing the world”. This resonates with what Paul [Kingsnorth] is saying about ecocentric worldviews and Robinson Jeffers’ idea of ‘inhumanism’. To me, this is contrasted by the discourse of sustainability where essentially nature is there to be managed…

DH: One of my critiques of sustainability would be that it has almost entirely sold itself on a resource-based model [the ‘resource based model of the commons’ referred to here is an idea of Anthony McCann]: a way of looking at the world in which you can no longer see a mountain, you can only see a stockpile of mineral resources that are capable of being traded on futures markets even before they’ve been pulled out of the ground. I mean, that comes out in the interview with David as well. The other issue with sustainability, which I thought you might be about to touch on, is how quickly it comes to mean sustaining the world as we know it, failing to distinguish between “the world as we know it” and “the world, full stop”. And the irony when it comes to innovation is that virtually the entire discourse on innovation that we have is part of “the world as we know it”. And therefore, the genuinely radical, disruptive kind of “innovation” – for want of a better word – that is coming, includes the disruption and the uprooting of a rather shallowly-rooted discourse and set of models for talking about what we call innovation. I sometimes feel that theologians might have more to tell us about the real kind of innovation that is coming than innovation theorists!

JDG: It is almost like we can’t see what is new, outside a linear trajectory…

DH: Absolutely. The night before the riots started [in London], I was starting work on an essay which I put to one side and will come back to. It started with the proposition: “The game is almost over. It is time to remind ourselves that it was a game, and that we are the players, rather than the pieces with which we have been playing.” The game, in a sense, is what we’ve known as capitalism. It’s the way of viewing the world, and the actions that follow from that, where you treat reality as made up of things which can be counted, measured, priced. And once you agree to that rule then certain kinds of behaviour become almost inevitable. And a lot of the stuff we’ve said about “human nature” is really about the nature of humans when playing that particular game. History and anthropology have a lot of material for us which shows that there are other constellations in which we can be human together than the ones which are normal under the rules of this particular game [as a starting point, see David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011)]. And as this unravels, then ways of thinking are likely to be useful or not useful to the extent that they have an awareness built in that there are other games that humans are capable of playing. Whereas so much of what comes under the heading of “innovation”, “sustainability” and many other prevailing discourses – well, it doesn’t look beyond the parameters of the game, it takes the game as ultimate reality, rather than just one of the realities that we are capable of socially manifesting.

JDG: And I guess what Dark Mountain is doing, in a sense, is opening up the playing field?

DH: And part of the importance of it being a space of ambiguity – and an unhurried, otiose space, a space of otium, schole, leisure – is that it allows for that kind of coming-into-awareness of the arbitrariness of the rules of the particular games that we arrive familiar with. That can include the big game of capitalism, the game of sustainability as we’ve known it – all of these things are open to this kind of challenge. And then [Dark Mountain is] a safe space in which you can begin imagining and practicing other games. In a sense… you touch on the idea of it as a philosophical project, certainly for me there is one aspect of a philosophical project that I feel I’ve been collaborating with a large number of people on, which is a project to create a more complete – that has to be qualified carefully – but a more complete postmodernism than the one in which we were schooled when I was studying English literature. The postmodernism we’ve had is heavy on deconstruction but has almost nothing to say about what comes after. And in that sense it reproduces one of the classic moves of modernity, which is to treat analysis as ultimate, rather than as something transitive.

My unwritten thesis from the end of my first degree was on this famous passage in The Tempest, the ‘Our revels now are ended’ speech. Prospero starts out trying to explain to his new son-in-law that he can distinguish between what is real and what is not real, so that there is no need to be freaked out by this magic performance he had just conjured up. He’s making this classic modernist separation of: “I can divide reality, I can divide experience into real and not real.” And what happens is that, within twelve lines, it unravels to the point where even “the great globe itself” is insubstantial. He’s gone from trying to reassure his son, to vexing himself. Because as soon as he starts pulling on that thread… it is the same pattern that happens philosophically, it happens from Locke to Hume in the early eighteen century. Newton has just shown us a scientific, rational frame for these things that where previously mysterious, we’ll be able to follow this all the way back to God – which is great, because then we won’t have any more religious wars, because we will have found a scientific explanation of the whole of reality. And instead, what you end up with is the radical scepticism that Hume arrives at.

Finding our way out of that philosophical bind that we kept getting ourselves into… for all its professed radicalism, mid-twentieth century/late-twentieth century postmodernism and poststructuralism and so on repeats the same pattern. So yes, I see Dark Mountain – not on its own, but in common with a whole patchwork of other outbreaks of philosophical improvisation – as opening a space where people can step outside of their games, with the ability to choose what game we play next, and not be trapped in a privileging of the negative – the error which sees the fact that you can step outside of the game as meaning that nothing is more real than something – in other words, that meaninglessness precedes meaning. Rather, we could imagine a condition which is neither meaning nor meaninglessness, which precedes them both…

JDG: So, when you unravel all meaning, you end up with an empty world, there is nothing there…?

DH: Yeah, and what happens next? In a sense, all of that stuff is a re-enactment of what is described in the classic form of a shamanic initiation. The experience of the initiation is that the teacher cuts the student’s body to pieces, and then they are re-born in a new body. It is what is described in the Hero’s Journey [Joseph Campbell], where the hard part is never actually getting far out, to the point of complete deconstruction of everything – or, the journey into the underworld. The hard part is always the last step of the way back, crossing the threshold back into social reality, and bringing something back across that threshold. Succeeding in the innovation, in the sense that your journey to the underworld – or to outer space, or wherever it is – doesn’t leave you dissociated and unable to talk to anyone, or unable to experience or create meaning. It allows you to bring back something that retains it’s meaning into the ordinary social reality, as you close that journey. And it is always at this threshold that the bag of gold turns into leaves or dust, as the hero crosses the last hill back to his village, from which he set out at the beginning of the story. That’s the hard part – and modernity has valorised the ‘out there’ part, rather than the bit that is genuinely hard.

JDG: Some of the things you are saying reminds me a bit of other currents, like Ken Wilber and the ‘we’re on the cusp of a new consciousness’ kind of thing. I am interested in hearing how that contrasts with what you are talking about.

DH: Well, I’m suspicious of overarching theories like that… And what I’ve been trying to express here might sound like a grand theory, but it’s intended as something more like a set of stories, an unfolding improvisation, or a map that one traveller sketches for another on the back of an envelope. It’s not intended as definitive. I was thinking about the singularity, which is a sort of geek’s version of The Rapture – at least in its classic form, in which people imagine technology achieving a kind of united consciousness. I’m thinking, too, of the unscientific ways in which people use the concept of evolution and talk about how we’re “evolving into a higher state of consciousness”. All of these seem to be trapped within the linear progressive story, which is the thing that we were really trying to hit in the manifesto, to say ‘that’s part of the game which we have to step out of’. And in a sense, the linear progressive story is the valorisation of the ‘out there’ moment. To me, a reconciliation of the linear and the cyclical is part of the game that I’m inviting people to. A lot of those things – and I don’t know much about the Ken Wilber stuff, but the little bit of contact I’ve had with it just slightly set me on edge, because it feels like it is trapped in a master narrative, in linear progress, in a fantasy of evolution as progress, rather than evolution just as an endlessly unfolding game, and one way of describing that endlessly unfolding game.

JDG: So, how do you see Dark Mountain as being different from other social movements, say Transition Towns or Open Source Ecology?

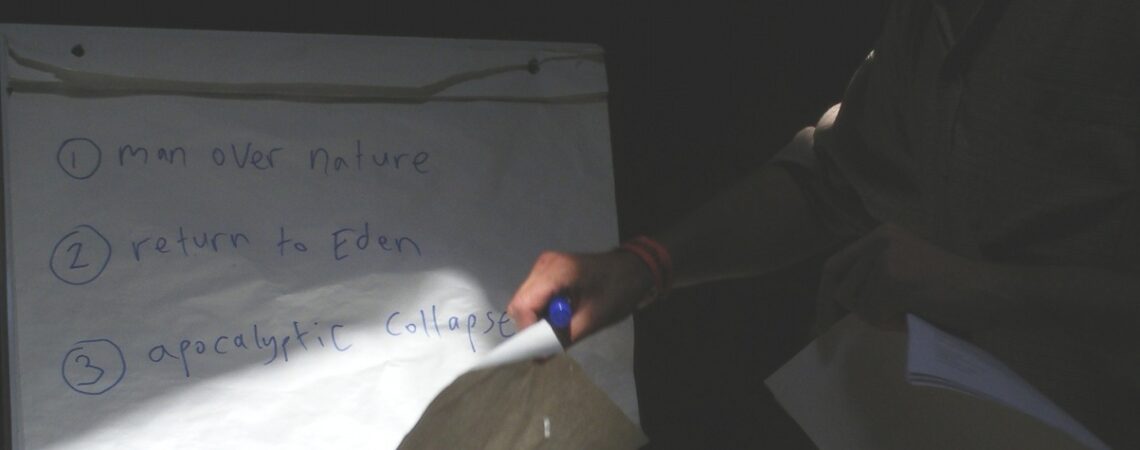

DH: Very much the emphasis on deep cultural narratives and choosing to address that, while explicitly renouncing a progressive or developmental linear meta-narrative. Because I think that, on the one hand, there are lots of places where people tend to be more focussed on the technical or “hard” end, rather than cultural or “soft” end, of the mess we are talking about. While on the other hand, when people do focus on the cultural, they tend to be heavily determining it with some big narrative, so… you know, I don’t know much about ‘The Work That Connects‘ for example – I know that it has been influential in the Transition world – but my impression, from a distance, is that it imposes a stronger pre-formed narrative on people’s engagement with the cultural and, if you like, the ‘spiritual’ aspects of our situation, and is perhaps less willing to sit with incompleteness and puzzlement and brokenness, and not impose anything on it, than I hope Dark Mountain is.

I came back from the meeting with Dougald with a whole new set of questions. So, how do narratives translate into action? In what ways can narratives open up or close down conversations and actions? What is the role of diversity in stories of social change? And are there better and worse ways to tell stories of change?

On a personal level, the most important thing about the encounters I’ve had through Dark Mountain is that it has opened up new doors. And forged new connections. Whether you describe the realisation that the world cannot continue as it is in terms of running up against a wall, an ‘epiphany’ or a ‘peak oil moment’ doesn’t really matter, it’s scary. Don’t let it be lonely too.

We’re setting up Dark Mountain Norwich. If you live in the area, get in touch and join the conversation.