Words and images can change minds, hearts, even the course of history. Their makers shape the stories people carry through their lives, unearth old ones and breathe them back to life, add new twists, point to unexpected endings. It is time to pick up the threads and make the stories new, as they must always be made new, starting from where we are.

– The Dark Mountain Manifesto

What difference does a story make?

It is said that a child once asked Wittgenstein why people living at the bottom of the planet did not fall off it into the blackness of the universe. He is said to have drawn a picture much like this

and then turned it like this

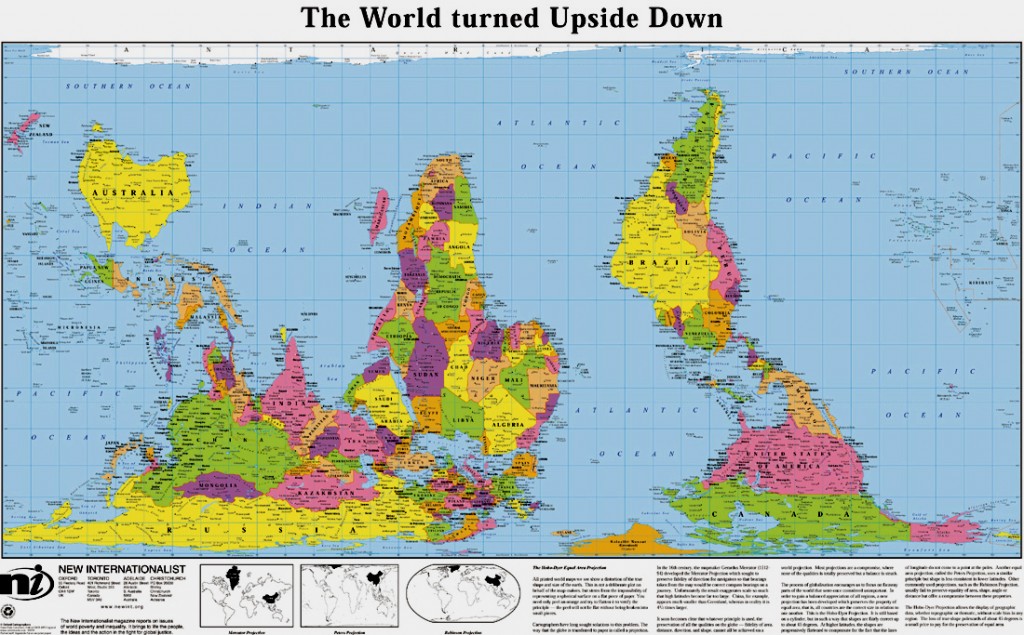

as a way of illustrating the depth of the child’s question and the profundity of the answer. When we get the meaning of this, something happens to our understanding of our relationship with the surrounding world (the story does not say whether the child was satisfied with Wittgenstein’s answer). Remember the first time you looked at this picture of the world

? In some sense the world was not the same to me after that experience.

Does it matter whether we explain people not falling off bottom of the planet in terms of gravity or in terms of the conventions of up and down?

Here’s another story. Once we lived in caves and mud huts, then we developed our brains and our skills and we didn’t have to live in caves anymore. Life became better and we became more intelligent and gradually we evolved to escape disease, hunger, and painful death. With the help of technology we have become masters of our destiny and as we gain more knowledge and skills we will be able to shape our future on this planet, Earth. We have seen back in time to the beginning of creation and we have mapped the skies and the galaxies. Our cleverness will take us into the future, even if there are bumps in the road along the way. We help each other. We’ve invented democracy. We fight to eradicate poverty. And we progress.

Contrast that story with this. God gave the world to Man as his Dominion…

Or this. The world is ruled by a small but extremely powerful elite who are bent on destroying the world…

Or, there have been five mass extinctions on Earth and we are currently living through the sixth…

The stories we tell about the world inevitably shape our thoughts and actions in that world, and determine our horizons, the limits of the possible, the extent of our sphere of influence. It goes deeper too because we also have stories about who we are and what the world is made from. Stories give us a place in the universe and a map that we can navigate through it with.

That is very well, you say. So we all have our stories and we all have different horizons. No big deal. It is that same old story of the half empty or half full bottle. Your loss, my victory.

But hang on a second. Because there is something more to it than our personal stories. Our common narrative of the world and our existence matters greatly to how we come together in our shared reality. And here is an example. I went to spend the weekend with a group of strangers (mostly) – all we had in common was a shared story about the world and what we are trying to do in it – and something magical happened. The world expanded and for a moment I thought I could hear the soil and the trees sing.

This is the story of the Dark Mountain Project and the adventure of Uncivilisation. The Dark Mountain Festival 2011 brought together around three hundred people who had all been inspired by authors Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine‘s literary manifesto. Calling for Uncivilised art and writing, the manifesto is a call to arms for ‘makers of things’ and ‘dreamers of dreams’, a cry for new stories that challenge the myth of progress and the very project of civilisation itself. A call which was heard far beyond literary circles and inspired a range of creative artistic, and social experiments. A cry which resonated and bounced across the internet and drew people together in storytelling.

It is, it seems, our civilisation’s turn to experience the inrush of the savage and the unseen; our turn to be brought up short by contact with untamed reality. There is a fall coming. We live in an age in which familiar restraints are being kicked away, and foundations snatched from under us. After a quarter century of complacency, in which we were invited to believe in bubbles that would never burst, prices that would never fall, the end of history, the crude repackaging of the triumphalism of Conrad’s Victorian twilight – Hubris has been introduced to Nemesis. Now a familiar human story is being played out. It is the story of an empire corroding from within. It is the story of a people who believed, for a long time, that their actions did not have consequences. It is the story of how that people will cope with the crumbling of their own myth. It is our story.

August 2011. The Dark Mountain Project manifested as a gathering in Hampshire, a weekend of conversations, workshops, music, talks, storytelling, performance art (for want of a better word), camp fire songs, and much much more. The festival website asked three questions: How do we make sense of our lives in times like this? Where are the stories – old or new – that help us reground ourselves? Faced with the loss of much we took for granted, where are the practical projects that offer hope and meaning for the times ahead? And these were the issues we explored over the two days the festival lasted.

From the moment I got in the car with Dougie, who had offered us a ride from the train station in Petersfield to the festival site, that exploration started. Pitching our tent we found ourselves engaged in conversations about agriculture, energy systems and national infrastructures. Over lunch we talked about narratives and social change and grassroots projects. In between sessions we quickly exchanged stories about ourselves and the projects we are involved in. And this was the brilliance of the whole thing. The conversations that came to us unexpectedly, timely and inspired.

The festival programme was made up of events with titles such as ‘Collapsonomics’, ‘On extinction’, ‘We can no longer afford to ignore the sacred’, ‘Living on the edge – and by the word’, ‘New myths for new worlds’, ‘Wild writing’, ‘Why forage?’, ‘Visions of transition’. From such a line up, you might think that our discussions where rather sombre affairs, but surprisingly (to me at least) all the debates and workshops I attended where constructive, engaging and galvanising. The subjects weren’t exactly cheerful but then we don’t live in a very cheerful world. And some of the talks were depressing, like the one on the ongoing theft and murder happening in West Papua, but we were able to talk about in a direct way without giving in to despair. I think the underlying ethos of creating “[w]riting which unflinchingly stares us down, however uncomfortable this may prove”, instilled a sense of having dispatched with false hope and dishonest optimism and looking reality in the eye without pretence. From a project which I’ve heard described in ‘doom and gloom’ terms more than once, grew a festival which was full of warmth, friendship and stories that nurtured our spirits. Stories that reflected so many different facets of our times.

There was Arthur Doohan and his experience of working as a banker. He explained the structural nature of the ongoing financial crisis through his personal account of how banking as a system structures and transforms personalities. Listen: I want to tell you a story about – everyone knows Fred the Shred – I want to tell you a story about a different Fred that I used to work with. And Fred was as nice a guy as you could possibly meet for an American. He was Minnesotan, he looked like a Viking, he was blond, he has funny, he was kind, he was a Democrat. As soon as he had made some money in banking, he wanted to marry his redheaded farmer’s daughter girlfriend and go back and get involved in Democratic politics back in Minnesota. But at the time I was working with Fred we were trading emerging market debt. Distressed debt of Brazil, Nigeria, Russia, Poland, all that kind of stuff. And it was a hairy market and very strange things used to happen from time to time. And because we were trading in the London office, things that happened in South America would get called into us first. And we had one very strange morning when literally the phones started going bananas as we walked in the door. It was about five o’clock in the morning in Venezuela, but nobody was up in New York so they were calling us, and they were all trying to sell everything. In the middle of trying to get some sense out of the chaos and the orders that were coming in, finally some news came through and it turned out that there was an attempted coup going on in Venezuela [… ] And, as I said, Fred was a really lovely guy, very nice, someone I used to drink with and have some fun with. He and I were strange fish in a room full of sharks, as inherent lefties we had bonded. But Fred is there, we are all two phones in our hands, screaming orders, trying to do deals, and the next thing I hear Fred saying something that absolutely brought me up short. Fred said, “Hey guys, I’ve got a client on the phone here, his house is on the other side of the presidential palace, and he sees the presidential guard shooting people in the street. This has got to be good for us” […] I just remember hearing Fred say that and just stop and turn around and look at him, you know, I couldn’t believe that nice Fred, absolute gentleman, heart of gold, wasn’t a right-winger, wasn’t a neo-Nazi, but in that extreme situation, where things are highly structured, highly evolved, the pressure on Fred and the reaction that gets pulled out of you is not the actions that people normally have […] That’s how banks have got evolved, that is the corner that they have been pushed into.

There was Eleanor Saitta and her story about her friends at a communication agency which has spent the last three years helping people to tell stories through alternative communication channels in places like Iran, Egypt, Libya, and Syria: Telling stories, telling the truth, in the face of oppression and in the face of systematic breakdown is an act of war. It is the way we help others share our reality. To share the truth of a contracting world in the face of systematic refusal of awareness. It is one of the only truly effective ways to shape our world. This weekend, while we sit here among these lovely English trees, thousands of people will take the streets in Syria to tell their stories, to try to shape their world into one which will support their freedom and their lives and their future. They will be answered by machine guns and mass graves, by snipers from the rooftops when they step outside, and by a world in which one person in ten turns evidence to the police. And yet they will not take up arms because their story is one of non-violence. My friends at [the agency] are not yet on the frontlines in Syria, but they know many people there very well. And even fighting that war at a remove can tear you apart. Last week, one of the core team almost killed himself after three years of desperate fighting. Three years of watching his contacts and his friends die. He stopped by Lands Memorial at the camp [Chaos Communications Camp] and he listened to the stories that people told. Stories of hope, and of bravery, and of loss. And he decided to live. I call on each and everyone of you to take up arms. See the world as it is and tell your stories.

There was Sharon Blackie and her poetic story of moving away from the humdrum of city life to the Outer Hebrides, learning to croft and setting up a publishing company. Listen to her discovery of a quality of connection with place that our world has largely lost: “… there are various definitions of the word witness. There is one that I like from middle English – which is a different sense from the sense I am talking about predominantly – which means a word or a thing whose existence attests or proves something, a token. And in a sense I suppose that is what we are trying to do, to show that there are authentic ways of living, where you can step out of certain aspects of the system, you can be something different, and your values can be different. The other thing that we are doing is witnessing in the more common senses, and that is in the sense of someone who can give a first hand account of something. Somebody who watches something. And witnessing in that sense is something that storytellers and shamans have been doing for centuries. It is more than just watching it in a passive sense, it is watching it in a way that kind of holds it, if you know what I mean by that. It kind of keeps the place alive […] by actively participating in a place like that, I can’t think of the right word, it is more than participating, it’s that connection with it, there is a sense in which you keep it alive. And in the same way that we need to keep stories alive, we need to keep that connection going so that somebody can be out there saying “yes, we can do it, it is possible, look I’ve got it, here it is, it is all about this”. In the same way that we need to tell the old stories and to keep those alive, we need to keep that sense of connection alive.”

There was Vinay Gupta and his meditation on death and life in conversation with Dougald Hine: “I’m forty and I am just beginning to notice physical problems which will probably not heal. Right, they are very early signs of genuine ageing, but eventually I’m going to have enough of these little glitches that my body stops working completely. Damn, that is not going to be any fun […] But I can avoid pretending it’s not happening. And as I get older and older and older, and death comes closer and closer and closer, you know, it is going to become a predominant part of my experience. It is going be watching the wall coming closer, and I am not going to blink […] it’s the understanding that you’re standing on the rails and there is a train coming directly towards you, and it is going to run you over, and you must not flinch. Because as soon as you flinch you have come out of contact with reality, and you are now living in a dream world […] it is going to hit you and there is nothing you can do about it, so you might as well get on with life in the full knowledge of death, because that is the only way you can actually be in contact with being alive. Rather than your model of being alive […] If you know you are going to die, you think about what are you going to leave people behind you, how have you treated others and, you know, what is your life for? […] If we are all going to die, what are we going to do together while we live? Is it really forty hours a week of nine to five for forty years? Is that the best we can do with this?”

And there were about three hundred others, sharing stories and opening up new spaces in each other. In a way, it felt like we were keeping each other compos mentis through storytelling. I came to the Dark Mountain festival with a notebook and a dictaphone thinking the project could make a case study in my PhD. Sitting in my house back in the everyday, listening to the recordings from the weekend, it feels like stories do make a difference. During those two days something was kept alive, was nurtured, within us and between us. I am not sure how to put it. I am not even sure it has a name. But I think it is what Roger, my festival neighbour, talked about when he said: “… sometimes one can feel overwhelmed by the problems of the world, and I go away from this [festival] feeling less overwhelmed, and thinking ‘no, perhaps all these ideas I have aren’t so silly after all, and I should carry on pursuing them’ […] There are projects which I want to start getting moving which will… coming here makes me feel more like I am going to do them.” Maybe that is what Dark Mountain is really about. Supporting each other as we journey into the future. My other neighbour Ana, whom I first met in Dougie’s car, put it thus: “For me Dark Mountain is a meeting point where… really, the main point is listening, is hearing other people. Seeing how they do things, and then how that can help me do my thing.”

But I don’t think that the Dark Mountain Project simply reinforced the stories we all came with, it was challenging and demanding as well. And at different points I had to accept that my version of the world wasn’t the most accurate. It gave me new perspectives but it is not always an easy process to find a new view. Perhaps the Dark Mountain Project is like Wittgenstein’s slight of hand when he turned the picture upside down and showed the child that to someone standing on the other side of the planet, she was living on the bottom. It is a different narrative of the times we live in, one which favours honest observation over technical answers, and one which says it as it is. Things are not going so well. And if we don’t start living differently in the world, if we don’t start living by different stories, things are not going to get any better. That is not easy.

But first of all, the Dark Mountain Project is the crumbling of myths and the formation of others. It is what we are currently living through. In this way, the uncivilisation festival took me to the Outer Hebrides, through economic collapse in Iceland to the overcrowded prisons of Russia, to civil unrest in Tottenham and squatting around London, on a sinking sail boat across the channel, and to the songlines of West Papua. I now think of it as giant watercourse, a flood of stories, thoughts, ideas and reflections, and we were all contributory streams flowing into the river gathering pace as we went down towards the ocean.

All stories and quotes in this post are reprinted with permission from the authors.

When the game is rigged and the ref is corrupt

Perhaps what we should fear most in this age of Collapse is the strain on...